Reichspogromnacht

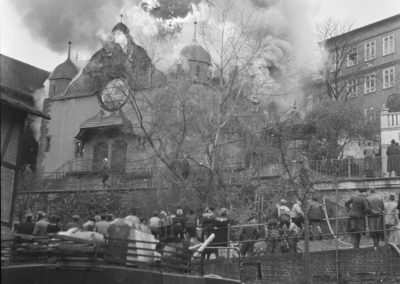

The synagogue’s destruction was captured by the amateur photographer Erich Koch (1914–1986) from Siegen. Koch, a businessman by profession, arrived at the scene when the building was already in flames. The rights for the photo series with 26 shots are held by the Siegerländer Heimat- und Geschichtsverein (the Siegerland society of local history). The Aktives Museum association presented the pictures to the public for the first time on November 9, 2018.

Comparatively late, around noon on November 10, the Siegen synagogue, too, fell victim to the flames. The new SS Hauptsturmführer in Siegen, the teacher Heinrich Lumpe, had obviously not known of a synagogue and was only made aware of it by a call from his superior. Immediately, Lumpe assembled a group of ten to twelve SS and SA men, whom he ordered to wear civilian clothes. In broad daylight, they entered the building and built a pyre out of wooden benches, the harmonium, and the preaching podium. The fire quickly spread, and the apartment of the janitor’s family caught fire. The firefighters concentrated on preventing the fire from spreading to the surrounding buildings. The numerous onlookers kept quiet; neither applause nor protest could be heard. Only a doctor from the neighborhood, whose patients included members of the Jewish community, shouted from the window, „What kind of a dirty job are you doing?“

Wolfgang Benz

The perpetrators then went to the Jüngst restaurant to celebrate the „Judenaktion“ in the SS’s regular pub. Six of them were charged in 1948 „with crimes against humanity and aggravated arson.“ The sentences were extremely lenient: Three men were acquitted, and three were sentenced to prison terms of a maximum of one year and two months, but these were shortened or even suspended. The justification of the verdict said that the defendants had merely been „tools of others.“ „Their insight into the injustice of their deed“ had been „considerably impaired“ by the „propaganda which they had been exposed to for years.“

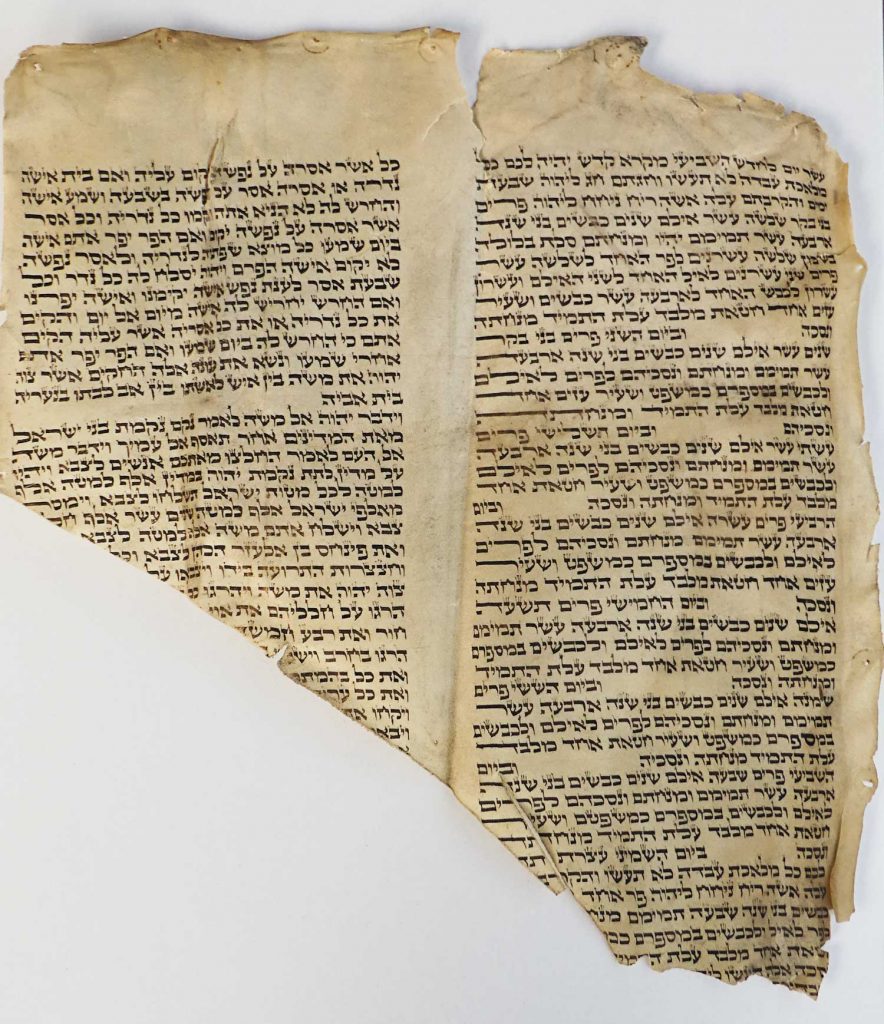

The fragment of the Torah scroll is one of the few things that remain from the Siegen Jewish Community. The piece of paper had been rescued from the debris by 14-year-old high school student Heinrich Kretzer. Heinrich Kretzer was one of the students from the city’s high school who were sent to the scene of the fire by their teachers to witness „the new era.“ Kretzer took the parchment, hid it under his sweater, carried it home, and pinned it in his closet: one must not forget what had happened, the student justified his courageous deed. Heinrich Kretzer died in October 1944 at the age of twenty as a Wehrmacht soldier.

Half a century later, his youngest brother Rolf remembered the fragment: In the summer of 1995, the Aktives Museum Südwestfalen (AMS) had called on the citizens of Siegen to search for things from the Nazi era. Rolf Kretzer gave the page to the museum, where it can be seen today.

After the Pogrom Night, the number of Jews who wanted to leave Germany increased rapidly. Around 130,000 – as many as in the entire previous five years – left their belongings behind and set off for an uncertain future. Those who could, also left the Siegerland: by the time Jewish emigration was banned on 23 October 1941, about forty percent of the Siegerland Jews had left. Those who stayed behind were the old, the sick – and men who bore responsibility like Eduard Hermann, chairman of the Siegen Jewish Community since 1921. The small group of believers now met in his house for services. Hermann also had to conduct the negotiations with the Nazi authorities, who demanded that the congregation demolish the ruins and sell the property.

The congregation had to bear the costs of the demolition, and the property was sold to the city of Siegen for far less than its value on 20 July 1940 – almost exactly 36 years to the day after the synagogue was dedicated. In 1941, the city built an air raid shelter on the property. There was to be nothing left to remind people that a synagogue had stood here.

For the Jews who remained in Germany, the situation became increasingly unbearable. From September 1941 onwards, they had to wear a yellow „Jewish star“, which prevented many from leaving the house for fear of being beaten up on the open street. In October 1941, the deportations to the extermination camps began. At least 160,000 German Jews were not to return.

As late as September 1944, Jewish women from the Siegerland who were married to non-Jews or so-called half-breeds were deported to the Kassel-Bettenhausen concentration camp, a subcamp of Buchenwald.

When Heinrich Marburger, a miner from Müsen born in Fischelbach near Laasphe in 1887, learned of the destruction of the Siegen synagogue, he said, „This is the end of the Nazis.“ In justification, he quoted a verse from the book of the prophet Zechariah: „He who touches my people touches the apple of God’s eye.“ The city of Siegen was almost completely destroyed on December 16, 1944, and in further Allied bombing raids. On May 8, 1945, Nazi Germany declared its unconditional surrender.

Text: Uwe von Seltmann (2021)