The virtual reconstruction

of the Great Synagogue Warsaw

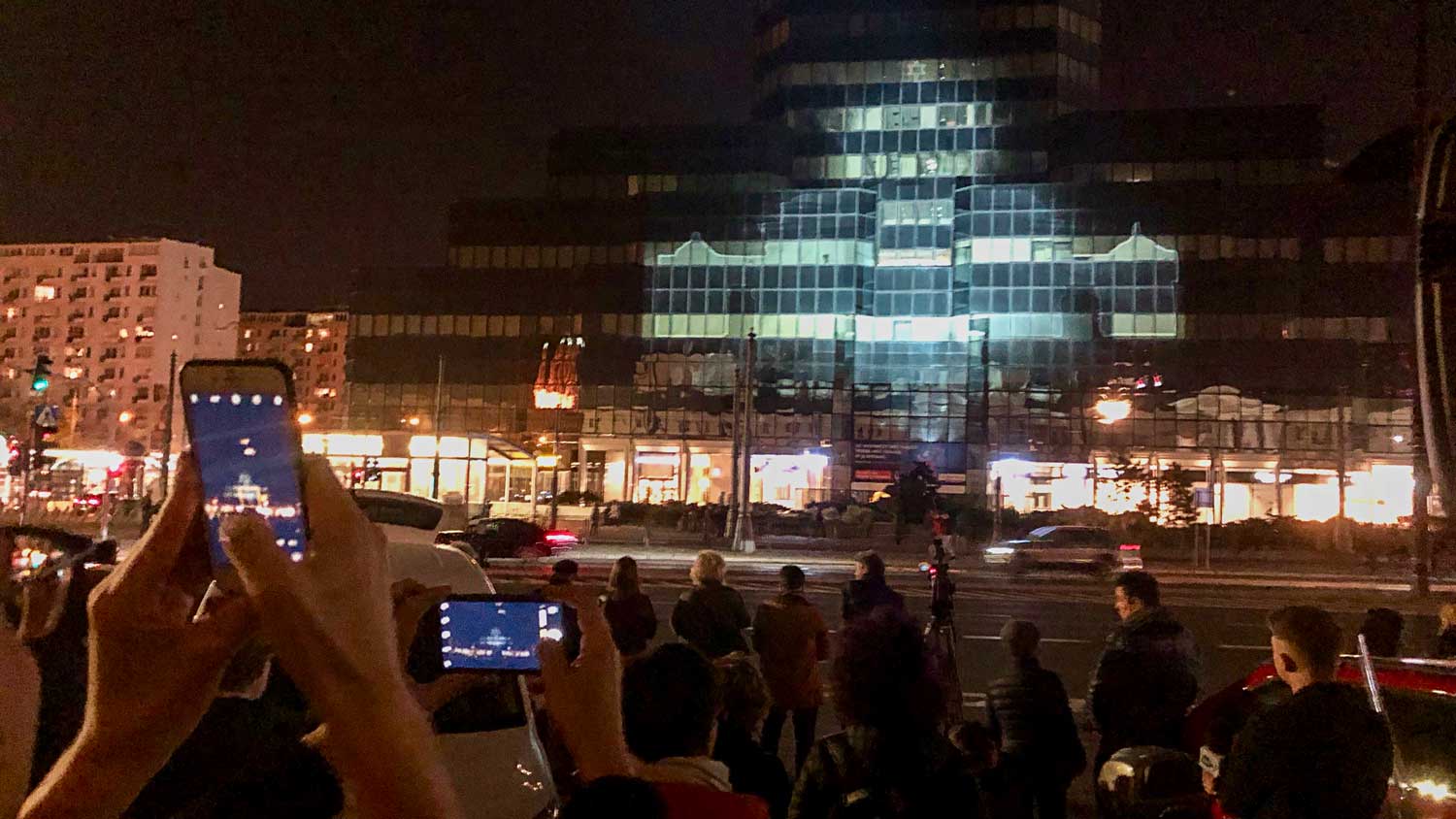

The photo shows the virtual reconstruction of the Great Synagogue of Warsaw, which was demolished on May 16, 1943, on the orders of SS General Jürgen Stroop. On its former site now stands a financial high-rise, on whose outer facade the video installation was projected.

The multimedia installations marking the anniversaries of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 19, 2018, and April 18, 2019, and – due to the pandemic – on September 26, 2020, were viewed by up to 7,000 visitors on-site and several thousand worldwide via live stream.

At the center of the open-air event in Siegen is the video installation with the virtual reconstruction of the Siegen Synagogue. This installation will alternate on the wall of the Hochbunker with the video installation for the Great Synagogue Warsaw. Why two installations? On the one hand, this is to show the connection between German and Polish Judaism; and on the other hand, because Warsaw has become a double symbol: It stands – next to Auschwitz – for the extermination of European Judaism by the Germans and at the same time for Jewish resistance against the National Socialist terror.

The virtual reconstruction of the Great Synagogue of Warsaw received worldwide attention and generated international media coverage. The photo shows the cover of Afn Shvel, a social-literary journal published in Yiddish in New York (July 2018 issue).

German and Polish Jews look back on almost a thousand years of shared history. It began after the Crusades at the end of the 11th century, and especially after the plague pogroms in 1350, when Judaism was largely eliminated in German territories. Survivors of the pogroms moved to the Kingdom of Poland, where they were welcomed with open arms. They took with them their language, Yiddish, which had developed around the year 1000 in the Jewish communities of the Rhine region. Over the centuries, several migrations in the opposite direction occurred: Hundreds of thousands of Polish Jews moved to Germany, some of them to Siegen after the First World War. Jewish life in Germany is inconceivable without Polish Jews: Politician Rosa Luxemburg (1871–1919), philosopher Martin Buber (1878–1965), literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki (1920–2013), and many more were formative for Jewish life in Germany. After World War II, two-thirds of the approximately 20,000 Jews living in Germany had been born in Poland.

Until Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Warsaw was one of the centers of European Judaism. In 1939, nearly 370,000 Jews lived in the Polish capital, almost a third of the city’s population – more than in any other city in Europe. In November 1940, the German occupiers established the Warsaw Ghetto, where they confined up to 450,000 women, men, and children to cramped quarters in inhumane conditions before deporting and murdering the inhabitants in the death camps; among them many German Jews. On April 19, 1943, primarily young Jewish women and men defied the deportation orders and rose up against the occupiers. Although inadequately armed, the Jewish fighting units fiercely resisted for weeks before the uprising was crushed. Only a few of the approximately 750 active fighters survived the Shoah.

For the 75th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 19, 2018, Gabriela von Seltmann developed a multimedia project that attracted thousands of visitors on-site and caused a worldwide sensation: On the facade of a financial high-rise, she resurrected the Great Synagogue with a three-dimensional video installation. Built in 1878, the landmark of Warsaw’s once flourishing Jewish life had been destroyed on May 16, 1943, on the orders of SS General Jürgen Stroop. What had begun with the destruction of the German synagogues on November 9/10, 1938, seemed to have come to an end with the demolition of the Great Synagogue of Warsaw. Stroop celebrated the destruction as an „unforgettable allegory of the triumph over Judaism.“

The video installation thus serves ultimately not to leave the last word to Hitler and Stroop – and thus to hatred, death, and destruction – but to declare publicly and emphatically: Judaism lives! We Jews live – and we do not hide, but show ourselves in public! And the Yiddish language, which three million Polish Jews spoke before the Shoah, is also alive!

The soundtrack of the video installation features an original historical recording of the cantor of the Great Synagogue, Gershon Sirota (1874–1943). Sirota was murdered at the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 19, 1943. A day later, Michał Klepfisz, a member of the Jewish Fighting Organization and friend of the leader of the ghetto uprising, Marek Edelman (1919–2009), was shot. Michał Klepfisz’s daughter Irena, born in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1941, is featured with an excerpt from her Yiddish-English poem Bashert. The poet survived the Shoah with forged papers in a Catholic orphanage. With her mother, who had also survived with forged documents, she came to New York in 1950, after four years in Sweden. A Polish translation of the verses will be read by Paula Sawicka, Marek Edelman’s close friend and co-author of the book Love in the Ghetto (Schöffling-Verlag, 2013), which has also been translated into German.

These words are dedicated to those who died

because death is a punishment

because death is a reward

because death is the final rest

because death is eternal rage

These words are dedicated to those who died

Bashert

These words are dedicated to those who survived

because life is a wilderness and they were savage

because life is an awakening and they were alert

because life is flowering and they blossomed

because life is a struggle and they struggled

because life is a gift and they were free to accept it

These words are dedicated to those who survived

Bashert

Excerpt from the poem „bashert“ by Irena Klepfisz